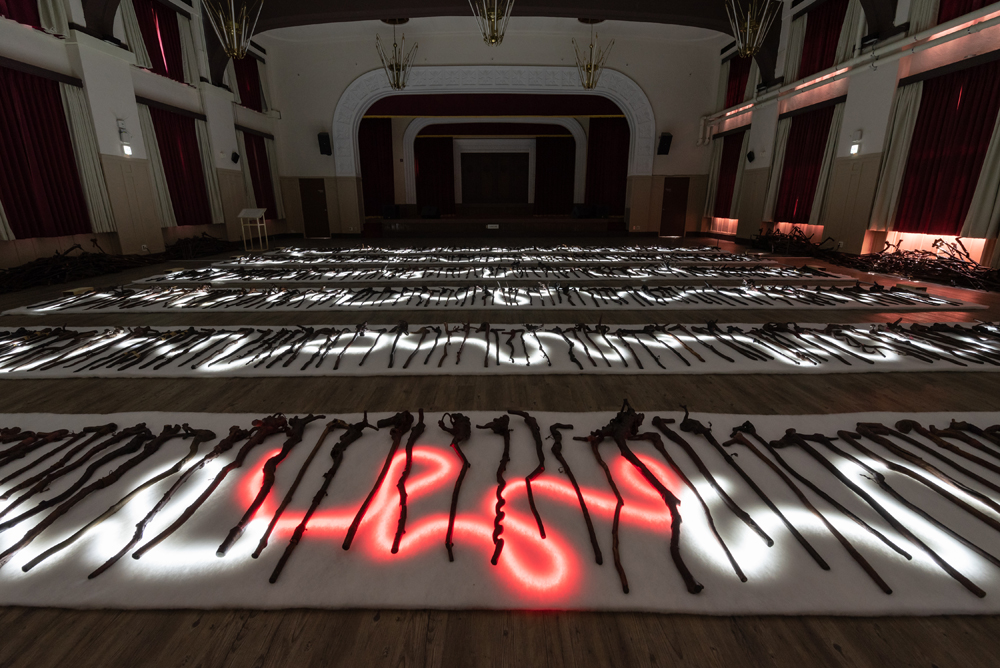

Mr. Eui Jin Chai and 1,000 Canes,

2014–20

site-specific installation view at May 18 Memorial M3 (former Conference Hall of Jeollanam-do Office) at ACC (Asia Culture Center)

Commissioned by Gwangju Biennale Foundation

‹채의진과 천 개의 지팡이›, 2014~2020

장소 특정적 설치

가변 크기

MayToday, (재)광주비엔날레 커미션, 국립아시아문화전당 민주평화기념관 3관 대회의실(옛 전남도청 강당), 광주, 한국

사진 크레딧: (재)광주비엔날레

임민욱의 장소 특정적 신작 ‹채의진과 천 개의 지팡이›는 한국 전쟁기 민간인 학살 생존자였던 채의진 작가가 만들던 지팡이들로 이루어져 있다. 이 지팡이들은 상처 입은 자의 버팀목과 같았기에 이제 한 걸음 더 나아가, 광주민주화운동의 의미와 방향성을 연결하면서 끝나지 않은 질문을 이어가보고자 한다.

고 채의진 선생은 1949년 12월 24일, 문경 석달 마을에서 벌어진 학살 현장에 있었으나 총에 맞은 친형과 사촌 동생의 시신 밑에 깔리면서 기적적으로 살아났다. 하지만 당시 어머니와 누나를 포함한 9명의 가족을 잃었으며 그 이후, 민간인 학살 진상을 규명하는데 한평생을 바치며 싸웠고 안타깝게도 2016년, 지병으로 별세했다.

고인은 살아생전 서각을 주로 했으며 이 지팡이들은 선물용으로 만들어지거나 미완성인 채로 지붕 위 간이창고 뿐만 아니라, 집안 곳곳에서 살림살이와 뒤섞여서 유기체를 이루고 있었다. 그는 “슬픔과 분노, 고독과 저주로 더럽혀진 삶에 맞선 쓰라린 투쟁과 통한의 몸부림” (채의진 작가노트), 자신이 수집해온 나뭇가지와 뿌리를 통해 “말로 다 할 수 없는 것들”과 소통하고자 했다.

한국은 과거사 진상 규명을 제대로 이루지 못했고, 소외와 낙인의 폐해는 오로지 민간인 피학살자 당사자들과 유족의 몫으로 남겨져 있다. 그러나 채의진 작가만의 저항 및 발화의 방식은 각별한 것이었기에 이에 주목한 임민욱은 이를 끊임없이 새로운 미학적 형식으로 바라보고 응답하고자 한다.

임민욱은 분단국가의 현실로 인한 이데올로기의 과잉, 압축적 근대화가 폭력으로 점철된 일상, 그리고 기억과 장소의 공동체에 대한 질문들을 사물의 배치와 장소 개입을 통해 비추고 있다. 그는 뜻밖의 사적 계기로 인해 한국전쟁기 민간인 학살에 대한 의문을 품게 되었고, 진실과 화해 위원회 주무조사팀장으로 활동했던 한성훈 박사를 통해 채의진 작가를 만나게 되었다. 그 이후 이 오브제들과 공명하게 되었고 일부를 위탁받아 작업하게 되었다.

2009년부터 ‘입을 수 있는 조각’ 이라는 이름으로 <포터블키퍼> 연작을 해오던 작가는 부표나 촛농, 깃털, 버려진 오브제들로 사물의 신체를 구성하고 사라지는 장소, 가려진 존재들과 함께 하는 유사 의식들을 통해 일종의 증언 기록을 시도해왔다. 그리고 이러한 작업들은 미적인 것과 윤리적 질문들이 불러낸 연루감의 딜레마를 수행하는 퍼포먼스 사물로 이어져 오고 있다.

이 지팡이들은 2014년 제10회 광주비엔날레 개막작으로 <내비게이션 아이디>를 선보였을 당시 <관흉국 사람들_입을 수 있는 조각들>과 함께 전시장 안쪽에 설치되어 있었다. 2020년 새롭게 배치된 이 지팡이들은 사물과 유언의 관계 속에서 (비)존재와 (비)장소를 소환하는 제3의 다리이자 파장이 되고자 한다.

Mr. Eui Jin Chai and 1,000 Canes, 2014–20

site-specific installation at May 18 Memorial M3 (former Conference Hall of Jeollanam-do Office) at ACC (Asia Culture Center)

Commissioned by Gwangju Biennale Foundation

Evocative and poignantly delicate, the canes in Minouk Lim’s new site-specific work unfold the perennial oeuvre of Chai Eui Jin, a survivor of the massacre committed against unarmed civilians during the Korean War. These canes not only represent their despair and sorrow, but also embrace the wounded. Furthermore, they extend the trajectory of the historical lessons of the May18 Democratization Movement.

On December 24, 1949, Chai miraculously survived a brutal massacre at Seokdal village, being covered under the collapsed bodies of his brother and cousin who were shot and fell during the rattle of gunfire. In total, he lost nine family members which included his mother and sister. Living through a great deal of pain, Chai enkindled the investigation of the truths in the civilian massacre until the time of his death in 2016. Thenceforth, the canes made by Chai remained dormant at his rooftop. Chai took on engraving practice during his lifetime, which resulted in the intense resonance of grief and suffering waged by his canes felt from every corner and object in the house as if they were brought together as a living organ. Through the roots and branches that he had collected, Chai was communicating with ‘things that are impossible to be rendered in words,’ in response to the ‘bitter struggle and mournful fight against the life tainted with sorrow, anger, loneliness, and curse,’ written in his note.

The Political and historical complexities in finding the truth of the past still pervade every stratum of Korea, and punishment of those responsible is still an unfinished quest. Hence, the stigma and feeling of abandonment of the victims, families of victims, and survivors are still present on their own hands to face. This is precisely what Minouk Lim has paid attention to and embodied in her work—how Chai resisted and unravelled the lingering traces of the past.

Lim seeks to address beyond the overarching ideological binary thinking and reality of fast modernization where violence finds its expression, through the assemblages of objects and intervention of places. After having been informed about the “National Bodo League” (or “National Rehabilitation and Guidance League”) incident, Lim began to question about the civilian massacres during the Korean War. With support of Dr. Han Sunghoon, a member and researcher of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Lim had met Chai and learned about his practice.

Lim explores various modes of creating records considering vanishing places and erased beings through different means of performance that may appear ritualistic. Since her ongoing piece—Portable Keeper, which she created in 2009 as part of her Wearable Sculpture series, she has taken materials such as buoys, paraffins, feathers and abandoned objects and turned them into the organs of her sculptures. In the resulting works, objects are embedded with performativity, allowing Lim to confront aesthetic and ethic dilemmas through them.

When Lim presented Navigation ID (2014) for the opening of the 10th Gwangju Biennale, the canes were installed in the exhibition hall together with The Hole-in-chest Nation_Wearable Sculpture. In 2020, these canes are re-articulated and exhibited in new display setting. They operate as the “third leg” and stimulus that evokes the notion of (non)being and (non)place and give relevance to the testimonies contained in objects.

(5.18 민주화운동 40주년 기념 특별전 'MaytoDay' 도록 글)